With all the talk of interest rates going up, one of the quiet factors that is starting to concern those in financial markets is the cost and availability of wholesale funding. This is their version of closely watching your home loan rate rise.

Wholesale funding is where big investors or institutional lenders provide debt to financiers who then on-lend this money to individual borrowers. Investors and wholesale lenders come in a few different forms. Many are big pension, superannuation and managed funds, insurance companies, or money market investors. Others in the market also include banks who need to keep a portfolio of well-rated and stable investments to manage their own liquidity requirements.

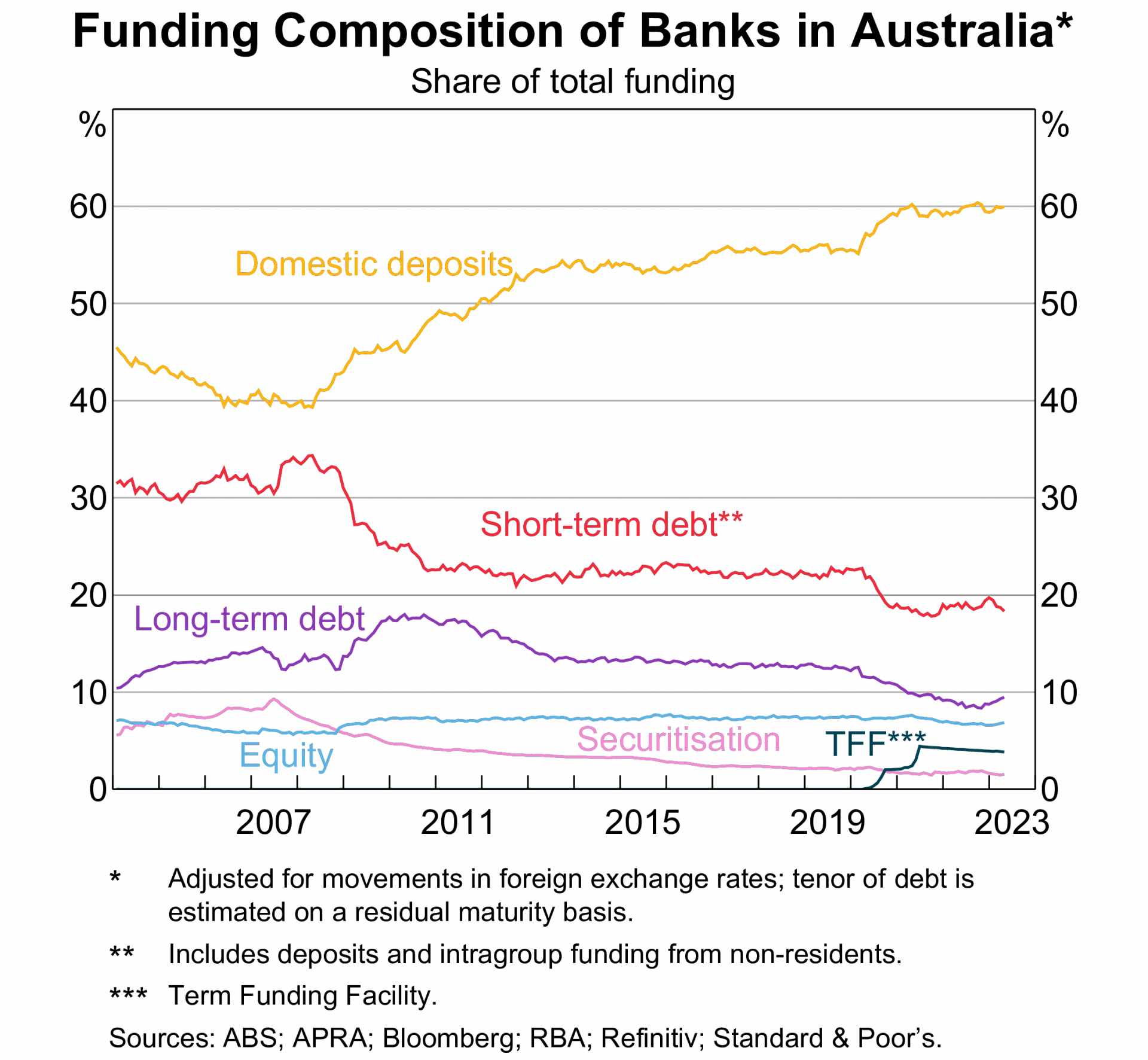

Some lenders need more wholesale funding than others. Australian banks have lots of deposits (which is just a form of short-term borrowing) which, according to the RBA in their May 2023 update, provides around 60% of their funding, upfront around 40% during the GFC (see RBA chart below). Deposits are a great source of capital for banks, but it introduces liquidity risk because they are either at call or short-dated term deposits. As a result, banks add to these deposits by borrowing longer-term from the wholesale markets. As banks have access to large sums of depositor’s funds, they can manage their wholesale lending requirements with more flexibility than other non-bank lenders. Banks can dip into the market when prices are favourable and have a pretty low risk profile which helps them access affordable wholesale lending at most times without too much difficulty.

(click image to open in full size)

(click image to open in full size)

Other lenders have a more difficult task in managing their funding. In Australia, those without Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) oversight and therefore without the benefit of being an Authorised Deposit-taking Institution (ADI) are unable to take deposits from retail investors and can only access corporate credit or wholesale markets.

When credit growth is running high and the savings rates of depositors are low – all lenders need to access well-functioning wholesale markets to continue to fund this demand for credit. Typically, in Australia’s past, this is the most likely scenario through most cycles. So, access to this type of capital is very important for our economy and has contributed to the growth and profitability of the lenders who operate within our borders.

But there are warning signs. Since early 2023, we’ve seen some ripples in the wholesale markets. Part of this stemmed from the aggressive tightening of cash rates by central banks worldwide which has affected all lenders. Capital available in the wholesale markets was also being repriced. These ripples grew to waves in March when some smaller banks in the US faltered and Credit Suisse needed rescuing. Suddenly wholesale borrowing got more difficult. Wholesale debt investors were wary of the solvency of smaller lenders and the risks of the recoverability of loans on their books, especially in commercial property and other areas of higher risk lending.

Unfortunately, these concerns have a habit of triggering other issues. As some wholesale lenders pulled back or tightened up their own credit appetite, the recipients of this wholesale lending suddenly needed to be a bit more cautious with their own loan growth. When there is uncertainty in the funds available to lend to your borrowers, most retail lenders also tighten up credit appetite or raise interest rates further to temper loan growth.

As multiple lenders all restrict credit availability in the market simultaneously, this acts as a handbrake on economic activity – which ironically usually means more bad debts and a greater risk of loan recoverability. While a first-mover advantage often exists – the first bank to tighten credit standards enjoys a period of moderating credit growth and easier liquidity management – this is more than undone when all lenders move in concert and precedes a more damaging vicious circle of tighter credit, higher bad debts, lower loan recoverability and therefore higher risk for wholesale investors, leading to even more restricted credit. This is commonly referred to as a credit crunch.

The Federal Reserve in the USA cited the rising risks of a credit crunch as their biggest focus in their most recent financial stability report.

Unfortunately, lenders with a large reliance on wholesale markets and who are also further up the risk curve lending to the riskier segments of the market are the first to suffer (think credit card lenders, unsecured personal loans, short term business overdrafts and lines of credit, start-up business funding, etc). These lenders may find their wholesale lenders refuse to rollover debt investments or demand higher interest rates to compensate for the risk. Capital is constrained or now far more expensive at a time when the underlying borrowers themselves also face general economic headwinds.

A flight to quality is underway, so banks with balanced lending portfolios and a low reliance on wholesale markets will still have access to depositors and should be able to balance the cost/availability of wholesale lending. Other lower-risk non-bank lenders will still enjoy wholesale markets access, albeit at a higher cost. The remainder, especially the non-bank lenders higher up the risk curve, will likely find themselves unable to access funding at all, or at least not at a viable cost for their business model.

Where to from here?

This wholesale debt market is a good forward indicator of expected future loan losses and bad debts and can sometimes lead the equity market in highlighting those retail lenders at risk. Even now three months after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and some other small USA-based regional lenders, equity markets are still punishing some lenders perceived to be at risk with the share prices of some lenders down 80+% this year where deposits (and presumably wholesale lending access) have already flown out the door.

We saw the worst of this in the GFC, where wholesale money markets froze, and again partly during the European Debt crisis a few years later. For some time all lenders, no matter how solid, could not access wholesale funds, which exacerbated the credit crunch. While we’re not at this point in this cycle, the wholesale markets are jittery and much closer now than they were six months ago. It would only take another notable bank failure to see this tap turned off to many lenders.

Where Australia can navigate a soft landing economically (or even a hard landing with confidence in the banking sector backed up by the RBA), it is more likely the lenders currently in the market will survive and resume lending. Unfortunately, the risks are rising for an uncontrolled hard landing where large sums of capital in the wholesale market suddenly are no longer available – leading to a severe restriction in credit in the retail market – our own credit crunch.

Hopefully, the non-bank lenders primarily reliant on wholesale lending can demonstrate confidence in their processes, credit decision making, and the quality of their loan book and recoverability. If they can prove they understand their loan book and its risks and have taken early action to manage any problems arising, then presumably their wholesale lenders will continue to provide support.

Those lenders showing early signs of bad debts or poor credit decisions will feel the brunt of the looming credit appetite reduction. Time will tell if it results in a credit crunch or worse – and we go back to conditions we experienced in the GFC.

For more information wholesale funding and BDO’s Debt Advisory services, please contact your local adviser.